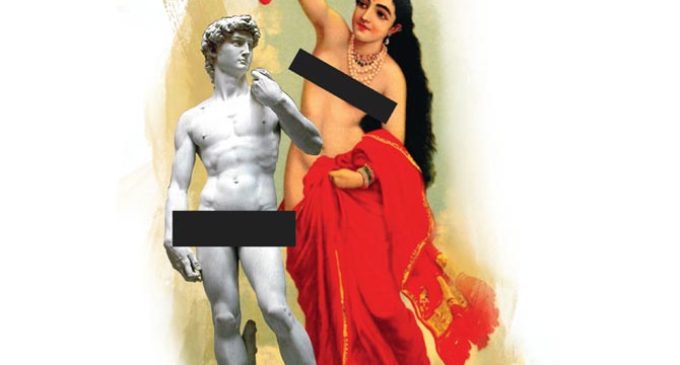

The Use Of The Nude As Social-Political Commentary

After Ravi Jadhav’s Nude, a look at how contemporary Indian artists use the naked human figure as socio-political commentary

May,06,2018(IST):As undoubtedly one of the most controversial films this year, Ravi Jadhav’s Nude has raised some serious questions through what it shows and, inadvertently, through what it chooses to stay silent about. At the heart of this Marathi film are two poor women who sign up as models for the nude study at one of India’s leading art colleges, Sir JJ School of Art. As one the last institutions in India where students work with live models, the practice meets with vehement protests. What’s interesting, amidst the case that the students make for the nude, is that the women, Yamuna and her aunt Chandrakka, in their absolute naiveté regarding art practices, raise the most significant questions. Yamuna asks — Why do art students paint nudes?

The film urges us to consider the nude, and the discomfort of the aam junta that surrounds it. It also urges us to consider how contemporary Indian art, no matter how diverse and fragmented it might be, evokes the naked body.Gallerist Mortimer Chatterjee sums up that up until the 1940s, in Mumbai, nude studies followed portrayals laid out in Victorian-era educational manuals, with JJ School as the most important centre for training students. “The nude body first really became eroticised around the early 1940s. From the late 1940s onwards, the nude body became weaponised, so to speak, in the work of FN Souza (such as the frank full frontal nudity of his self-portrait from 1948). The male gaze is certainly noticeable around this time,” he says. By the mid to late 1960s, in Baroda, the nude body was handled by artists such as Bhupen Khakhar to express ideas of

sexuality. “Increasingly, then, the nude becomes used metaphorically,” he says.

In 2016, DAG Modern’s three-storey building in Kala Ghoda hosted a large exhibition of works under the title The Naked and the Nude: The body in Indian modern art. Through 250 sculptures and paintings, curator Kishore Singh was able to distinguish the ways in which Indian Modernists engaged with the bare body. There was an untitled work by KH Ara, known as one of the first Indian artists to use the female nude as a subject, FN Souza’s Woman in a Corset, and a nude by Akbar Padamsee.

“From an art perspective, the nude has a voyeuristic tendency, but the ‘unclothed body’ moves away from salacious voyeurism to reflection,” says Singh. Artists today, he continues, are far more engaged with social and political concerns, their role with activism much more apparent. “Their practices are more driven by these concerns, so the pure nude hardly ever exists. I would prefer to use the phrase ‘the unclothed body’ for what we see in art practices today,” he says.

The difference in terminology is a significant one, and identifiable especially in performance art. In 2016, Naresh Kumar, a young Mumbai-based artist, showed his work, Stories My Country Told Me, at Clark House Collective in Mumbai, Gwangju, Korea, and at Villa Vassilieff, Paris. The work harkens back to revolts by indigo farmers in pre-Independent India, demanding fairer practices regarding taxes, loans and tenancy. Kumar covered parts of his body with industrial indigo for the performance. “The purpose of doing the piece naked is because when we talk about farmers, we cannot but look at their body. It is almost as if politics impacts their bodies. Look at the Kisan March from Nashik to Mumbai this year. We spoke a lot about their blistered hands and feet,” says Kumar. Shown alongside installations of farmers’ tools, the body, too, is an instrument. His naked body, says the artist, is his material.

Neither female nor male

The idea of studying the human body for academic purposes, says curator and art historian Lina Vincent Sunish, is purely a system by which students realistically portray form, as they would study a landscape or still life. What may be academically and anatomically correct, however, could be placed at a lower artistic value in contemporary times, she argues.

At the turn of the century, there were those like Sonia Khurana, says Vincent Sunish. Khurana, who is based out of New Delhi, had created a short video, titled Bird, in 1999. In this video, the artist stood naked on a pedestal, as if in an attempt to take flight. The work raised questions about womanhood, and, by presenting her naked body, rebelled against established ideas of beauty. “There was nothing subdued or decorative about that work; it was a true investigation of the female form. That said, the year 2000 onward, there have been largely fragmented representations of the naked body,” says Vincent Sunish, adding that many contemporary works open up the dialogue of genders, where the body may be both male and female, or neither, such as in Seema Kohli’s works.

Artist and curator Sharmistha Ray, who lived in Mumbai for over a decade before moving back to New York last year, cites Nalini Malani’s representations of nudes and nakedness, and Rekha Rodwittiya’s high stylised female nudes that embody her feminist politics as fine examples. She also recalls Abhay Maskara, the owner and director of the erstwhile Gallery Maskara, who started “the work of building a gallery program that championed controversial representations of the human body in contemporary art — male, female and queer — and the subjects of sex and sexuality, with promising artists like Shine Shivan and T Venkanna.”

Ray’s practice, which includes paintings and other media, has works that embody the female nude. “My representations of women, have, thus far, been of intimate partners,” she says. “These representations have been erotic and idealised at times, but the point was to be able to document a personal and human experience of loving, and to do that in a way that was tender, and poetic. But, I was also, very consciously, resisting erasure — so, in that sense, the work is very political, and very queer,” she explains.

Body under threat

In Nude, there is a scene in which an MF Husain-inspired character explains to Yamuna, as she models for him, that he paints nudes because he wishes to unearth the soul. One never asks why we paint horses nude or the birds, so why not a human? The answer these days is a more nuanced, often political one, but Ray says that it was generally the Modernists, including the artists of The Bengal School, who took more risks in their depictions of the human body. The scenario has worsened from when Padamsee fought a court case for his painting Lovers some six decades ago. Or, when Khurana was accused of provocation, mainly because of displaying an “undesired” body form (in Europe, Bird was better received, earning her recognition).

A few top-tier art galleries in urban India, says Ray, are the only spaces left for real dialogues in contemporary art and culture. “But, they too fear the potential repercussions of crossing the line; and specifically, the threat of violent attack,” she says, recalling two gallery exhibitions in Mumbai from the recent past that involved performance art and deployed the “naked” female body as a catalyst: Tejal Shah’s Between the Waves, at Project 88, in 2013; and Sonia Khurana’s Fold/Unfold, at Chemould Prescott Road in 2017. “However, given the explicit nature of Shah’s work, the exhibition wasn’t open to the general public. Perhaps it was a lost opportunity to further a conversation about the body and sexuality in the public domain, but can you really blame galleries for exercising caution?” says Ray.